Ever since I learned that the vaxx contents worked their way into the natural water supply, I’ve been really concerned with what might be happening in animal and plant life. Everyone who was vaccinated passed the nano from their bloodstream into the sewer system, which then got recycled back into local water supplies. But even before the vaxx, we were being sprayed overhead with nano that is the same or very similar to what is seen in the vaxx. And I’d imagine that the rate of the deployment of nano through various mediums is increasing in pace as more and more people are waking up. They seem to be speeding up the rate of deployment of various technologies designed to enslave us before a critical mass is reached and enough people wake up.

The first sample I ever looked at under a microscope was tap water from my bathroom sink. Thankfully I didn’t see any obvious signs of hydrogel, ribbons or chips in the tap water. Though I’m sure that as I take additional samples, eventually something will turn up. I know of at least one other researcher who found evidence of nanotech in a recreational pool. And of course many are now seeing it in rainwater. It paints a grim picture indeed. If it’s in the global water supply, then it’s only a matter of time that the nano infiltrates every crevice of life on earth.

Of course, I always retain the hope that nano researchers are suffering under a collective delusion and we are misinterpreting what we are seeing. For a while, it was the only way I could stay sane. It’s easier to believe that I’m just suffering the psychological aftereffects of battling a particularly bad case of Covid than it is to accept that the entire planet may be in danger. When I share my findings here on Substack, I always err on the side of the more prosaic, especially since I don’t have a formal background in biology. And so I’m definitely presenting a more conservative version here than what I could probably get away with.

Once it fully sank in for me that this nanotech ought to be showing up in wildlife, I started poking around in my backyard looking for samples. I tried cutting open the veins of very large, waxy leaves but couldn’t manage to get a decent droplet of liquid. I settled on some tiny wild raspberries that came from the same bush and varied in color from red to dark purple, depending on their ripeness, I suppose. I made two slides: a drop from a red one and another drop from a purple one. The two samples are essentially the same in presentation and results. Upon first viewing, I did not see any obvious signs of hydrogel, though there were suspicious “bubbles” that often later turn out to be hydrogel. More on that later.

The only notable elements in both samples are the presence of what “Will: Micronaut” here on Substack has termed “ghost filaments”. For context, I screenshotted the relevant images and text of Will’s posts so it’ll be easier to make side by side comparisons with my berry images. What he found in rainwater is very similar and perhaps the same as what I saw in my berries:

Full post from above image here

Similar to Will’s rainwater sample, the filaments I found in the berries were rudimentary compared to what we see in human body samples. Less solid, less fully-formed, thin and papery and more fragile. They were also much smaller and shorter in length than the fibers we see associated with hydrogel. Here are a few stereotypical examples:

Because my obsessive tendency to document conflicts with the need to hold the reader’s attention, scroll to the end of this post to see a photo dump of the rest of the images of these “ghost filaments”.

In the videos it’s hard to get clear resolution of these fibers because they’re so papery thin and delicate. Typically, fully-formed hydrogel fibers are thick and rubbery and strong. Because plants are full of natural fibers, it can be a bit difficult to distinguish artificial hydrogel filaments from organic fiber filaments. Here is a quick list that is helpful when distinguishing between natural and nanotech fibers. This is by no means an exhaustive list and is just a quick shorthand reference that I use when studying and attempting to classify fibers.

Qualities of artificial nanofibers:

interacts with or is in proximity to hydrogel (bubbles and sheets)

has dots inside of them (“quantum dots” or “mesogens”)

change color (typically red, blue, green or yellow/brown)

grow in size and/or change in shape

I’ve noticed that natural plant fibers are more papery or paper-like than synthetic fibers. The synthetic fibers typically present as solid-walled structures with clear boundaries. Below is a photo from Will’s Substack that compares a synthetic fiber next to a natural one (synthetic on the left and natural on the right).

Will wonders where these “ghost” filaments are nascent, developmental forms of synthetic filaments that, for whatever reason, are not able to evolve fully into a completely functional synthetic fiber. I’m on the fence as to whether these ghost fibers are aspiring synthetic ones or simply natural fibers. Natural plant fibers are varied and diverse and range greatly in quality and type. For the sake of simplicity, I’ll hone in on a single example of natural fiber found in all plants: cellulose.

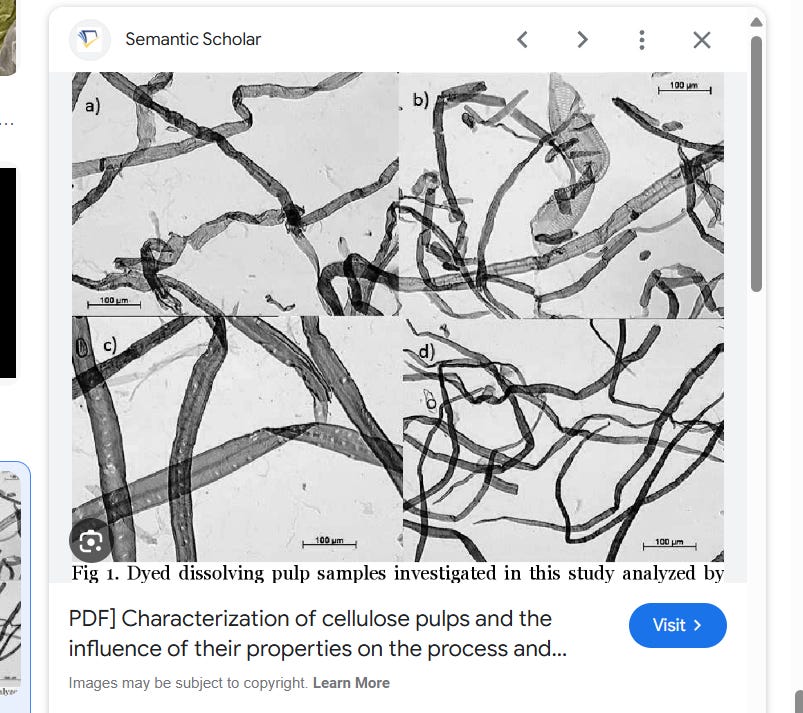

Below are some screenshots grabbed from Google Images showing some strands of cellulose under a microscope. (Credits for the image are mentioned in the text under the image).

As you can see, cellulose fibers are papery thin with weak structure compared to the artificial fibers that are thicker, rubbery, and plastic in appearance. The synthetic fibers usually reflect light and, when activated, emit light. Plant fibers typically present in clusters and in proximity to each other rather than standing alone like the synthetic fibers that present next to or within hydrogel. Cellulose often has pores which look like natural ventilation openings, whereas the “quantum dots” in synthetic fibers overlap each other because they are distributed 3-dimenionally throughout a fiber. They also blink, emit light, and move.

Below is an image screenshotted from a post by Ana Mihalcea that clearly shows the glowing dots inside of differently colored fibers. She has finally put her amazing work behind a paywall and I certainly don’t blame her.

My own personal opinion is that the vast majority, if not all, of the fibers I saw in the berry samples were natural fibers. Below is an image of a berry fiber with dots that are quite obviously pores stereotypical of cellulose:

Perhaps it is just wishful thinking on my part that these fibers are natural, but I have to cling to some hope that not all of nature on our planet is ruined.

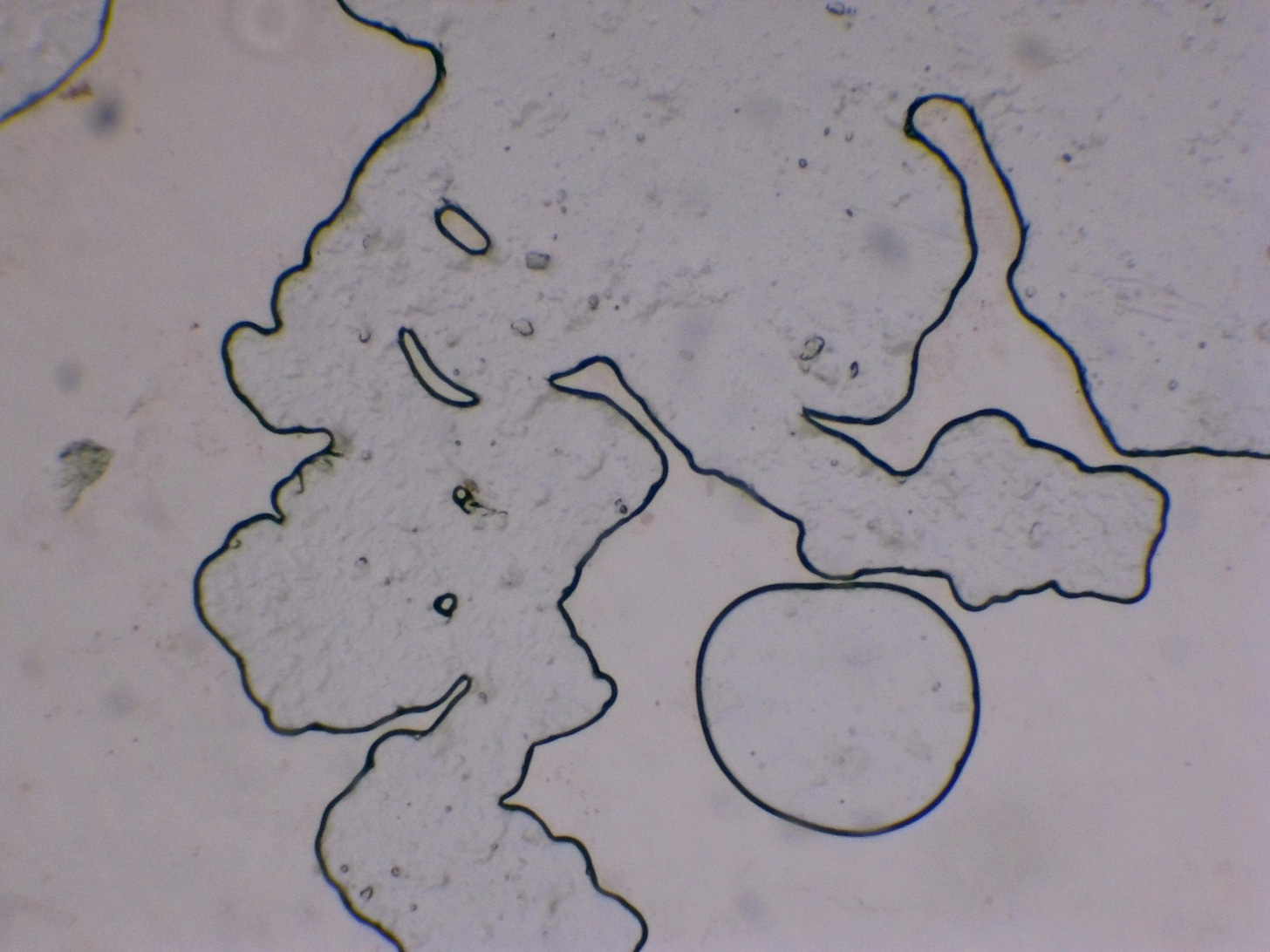

Other than the fibers, nothing else was distinct about the samples upon first viewing. There were what appeared to be ordinary bubbles, though I kept a close eye on them since we know that what at first appear to be harmless bubbles often transform into bizarre shapes and even crystals and chips at a later stage. The bubbles in my berry samples sadly did take on the stereotypical shape of hydrogel after a few days of sitting on the slide, but have not evolved in complexity or formed into crystals or chips going on one month now. They seem stabilized in the current form you see below:

There also seems to be much less hydrogel present in the berries than in human bodily fluid samples. So perhaps there is a glimmer of hope in that the evolution of the hydrogel is apparently stunted in these berries and hopefully all other plants. Though of course more research is needed. A lifetime of research, really.

Below is a video of hydrogel together with the only clearly suspect fiber from both samples. This fiber is very long compared to the other supposedly natural fibers, has a plastic or rubbery texture/appearance, solid walls, and is in direct proximity to hydrogel. We commonly see fibers “trapped” between plates of hydrogel.

For me, the jury is still out on whether the majority of the fibers in the berries are natural or just stunted/semi-formed versions of artificial fibers. The fact that the hydrogel didn’t continue evolving beyond what you see in the video above might indicate that the fibers encountered a similar fate. The nanotech seems designed for human and animal biology, and so perhaps it cannot evolve as far in plants and other biological systems. Perhaps the berries simply didn’t have a high enough quantity of hydrogel to produce more artificial fibers. Or perhaps enough hydrogel was in fact present, but for whatever reason was not able to become fully activated in order to evolve the other aspects of the tech.

However, plants are abundant in natural fibers, and so perhaps most of the fibers I saw in the berries were just that. I’ll let you decide. And of course, more research is needed and is forthcoming. Thanks for supporting my work. Please share it around social media. I’ve also activated paid subscriptions that start at as low as $8/month if you’d like to support my ability to do more of this work.

End of post.

photo dump of more of ghost filament pics:

:)

Interesting Stuff! It seems like there quite a few of us picking up on the urge to start looking at this stuff, myself included. Some of the samples I've prepared and looked at, not all of which I've made a post about yet, and to be honest I'm not sure I have enough time in the day to write and look. It's a little frustrating, but looking through the microscope consumes a lot of time. I do want to write up at least something about my first experiences of seeing these 'filaments' for want of a better word. For me 'filaments' is a wide-open term which can include a diverse array of anything that is filament-like either natural or synthetic, cellulous plant fibres to electronic wire filaments as in bulbs for example. I would like to clarify what it is that you are calling 'hydrogel'? It helps if we are all talking the same language, so please if you can, direct me to one of your own posts or another's post clearly showing what I should be looking for in terms of identifying the phenomenon of 'hydrogel'. I have seen some odd things and hope to document them soon...